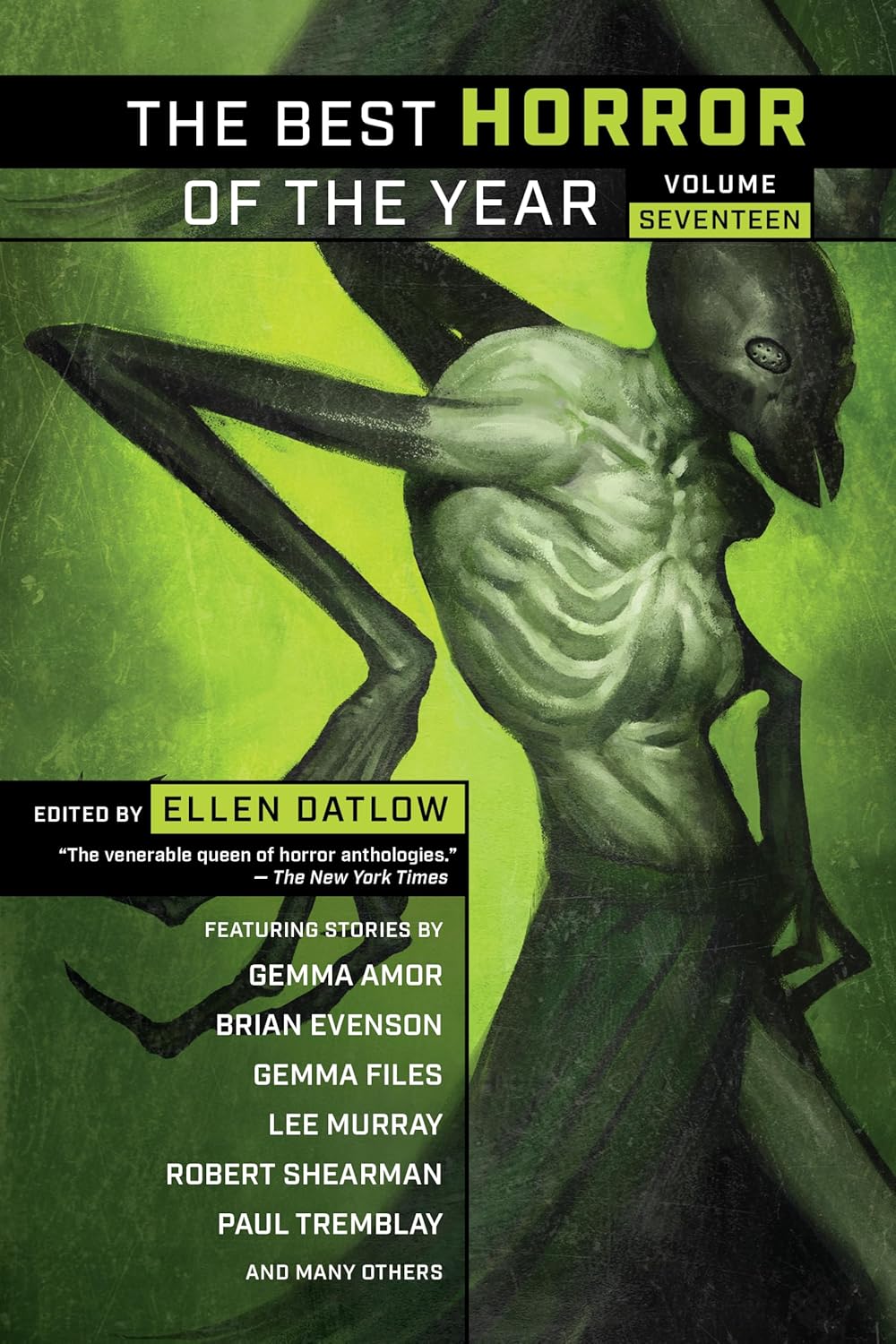

All Alone, On The Edge Of (Best Horror of the Year) 17: The Best Horror of the Year, Vol. 17 (ed. Ellen Datlow)

Let's do this. Spoiler alert: These stories are all good.

Blessed Mary by Stephen Volk

Synopsis: An expectant mother brings her husband to her Welsh hometown for Christmas, but the tradition of the Mari Lwyd, together with a secret from her past, may spoil everything.

Thoughts: It would suck to be a Stephen Volk story set at Christmas because you're always going to be compared to your successful big brother Ghostwatch. Volk gave us one of the greatest bits of British Christmas horror several decades ago with that terrifying, reality-warping BBC special; if you haven't seen it, you need to.

That's a pity, because "Blessed Mary" is a fine story itself, and properly Christmas-y. The Mari Lwyd is such a freakishly incongruous Christmas tradition (see also: Schnabelperchten) that a lesser writer would coast on that, but Volk ain't lesser. Of course, he leverages the bizarre imagery of the Mari Lwyd, but he also mines a strong vein of outsider's unease in a Straw Dogs-lite way, and grounds everything in a realistic, mundane threat. Along the way, there's loads of local and historical flavor. And the final few paragraphs are nauseating in the best way.

Mrs. Crace by Cliff McNish

Synopsis: After their mom dies in the Blitz, two children are raised by their distant, austere father and their mysterious nanny, Mrs. Crace.

Thoughts: McNish begins this story with a shout-out to Robert Aickman, which does a lot to put you in the right frame of mind for what's coming.

Aickman's stories are an odd mix of the conservative and the radical. The odd diction and sentence structures, the pace, and the understatement all bespeak an older-fashioned kind of ghost story, but the weird use of language, the fragmented and ambiguous storytelling, and the not-infrequent presence of perverse sexual overtones all feel experimental.

We have much of that here, as well. The prose is more lucid than Aickman's could be at times (not a criticism of Aickman--I love the indirect and weird ways his sentences could advance a story like knights moving L-shaped across a chessboard), but the story has some structural idiosyncrasies, and then there's the matter of the content. And that content is shocking. It's not graphic, which makes it more effective: McNish gives us enough puzzle pieces that we can figure out what the overall ghastly picture is without having to tell us--and he leaves some of the details out for you to draw in yourself.

A Lullaby of Anguish by Marie Croke

Synopsis: Antonia and Cassia followed their photographer dad's footsteps and made a name for themselves with their exploitative pictures of the "sea children". Now they're feeling guilty, but someone wants to reopen their past.

Thoughts: If you pushed me, I'd say this is the best story in the book. I have never read anything quite like this. If you write, even a little, you surely know the feeling of reading something and thinking, "oh shoot, you know, I wish I had written that story! I could have written that story! I've had that same idea!" There's another feeling, though, which is "wow, I never would have thought of this."

This story has stuck with me the longest; the ideas of two young girls Diane Arbus-ing their way through a miraculous waterworld, and producing pictures of crying selkie boys with ripped skins and (most upsetting to me) a pile of broken teeth next to a starving baby leviathan are wonderful and horrid and I can't let them go, even if I might like to.

However, Croke doesn't just coast on the shock value of "girls are cruel and mutilate fantasy creatures." That would be the easy route to go with this material (if anything with this wild conceit could be considered "easy"), but instead Croke places it later in the girls' life. Normally I don't like non-linear storytelling, but in the context of this story I think it's important. The tortures of the sea children are unpleasant enough that we don't really need to see more than the little we do, and the details of the girls' rise to fame on the basis of the pictures would probably wilt into implausibility if told straight. More importantly, though, the moral universe of the story cries out for some sort of revenge for the sea children. The sisters' guilt is a good story, but I feel that if we saw too much of their younger selves tormenting the sea children, the catharsis Croke offers at the end would be insufficient. As it is, it's a good, EC-style ending.

Drive by Brian Evenson

Synopsis: She killed him and stopped the ritual and got away. But now he's right beside her in the car.

Thoughts: A hypnotic road trip to hell--unless, of course, we're already there. In some ways, this is as straightforward as driving down the same stretch of road for hours, even if the hints and obscurity and ambiguity and elliptical nature of things gives it an Evensonian edge. At its best, this story reminds me of the underrated horror anthology Southbound, which taps into the same limitless ability to make isolated highways a locus of horror.

Archies by Paul Tremblay

Synopsis: Paul's visit with post-hardcore legends mcgarnagle is overshadowed by the feeling that he's being followed. Is it "Archie," the pugnacious cardboard cutout at the venue?

Thoughts: Tremblay's story of a night gone wrong is quieter than many of the stories here, mcgarnagle's rock music notwithstanding. That gives it verisimilitude, and I wonder whether it isn't based on actual events to some degree (although hopefully Paul isn't getting stocked by a murderous piece of cardboard). In some ways, despite the contemporary setting, it's a pleasantly low-key traditional ghost story, which gets more mileage out of a door swinging shut than many writers are able to get out of a serial killer or an alien invader.

Sunk by Richard Thomas

Synopsis: Pursued by the cult, our protagonist races frantically to the sea.

Thoughts: Some people eat the ears off their chocolate Easter bunnies first; my equivalent is that I generally start a collection of horror stories with the shortest one I can find. For this book, that's technically "Sunk," but I put it down once I realized it required much more attention than I could give it at the time.

This is a dense stream of consciousness riff that mixes cosmic horror, body horror, Cthulhu cult shenanigans, and psychological breakdown. It is exhilarating and exciting. It's not just a gimmick, either--I was invested in the fate of this poor schlub, hoping they would make it out of the clutches of the cult and foil their scheme.

My favorite part, though, is one of the many details that Thomas manages to jam into the story: It's his haunting description of the beachfront hotels and video arcades. It reminds me of Dennis Etchison (the second time that's happened in this book), and of Charlie Grant's haunting, melancholy seaside apocalypse "Across the Water to Skye." It's the sort of thing that on its own could very nearly make a story for me. The fact that it's just garnish to Thomas' tale gives you an indication of how good this story is.

Less Exalted Tastes by Gemma Amor

Synopsis: A developer sets his sights on buying a massive Irish country house, but the last dregs of the wealthy family there have a proposition of their own.

Thoughts: Lush, lavish cruelty and violence here; in a way this forms the middle part of a triptych of exquisite, high-class suffering in the collection (the Croke and Shearman stories are the left and right sides). And, speaking of extreme art, Amor's description of the carved wooden staircase-cum-monstrous hunting tapestry is a high point of the whole book.

The "bones" of the story are a well-trod scenario--this is at its core just another 'Old Dark House' setup--but even if it's familiar it doesn't feel threadbare. The protagonist's own greed and rapacity prefigures that of the family, while providing an excuse for him to be there, and giving us the eerie, erotic "negotiation" scene before the horror REALLY gets going.

There's finally a subtler bit of class consciousness within the story that has a bit of bite. I say "subtler" because while the premise of the story is "rich, aristocratic old families practice evil on an industrial scale," that kind of Gothic set up just feels more like a standard plot than any real meaningful political commentary; the "rich family that lives in seclusion to do depraved shit" is just a setup like "poor family that lives in seclusion to do depraved shit."

But, here's the bit that goes beyond just setting, and there's a spoiler here, so I'll move it to the next paragraph.

At the end, John is falling victim to the family. No real surprise, we all saw that coming by the end of the second page. He isn't alone, though. There's a window-washer there, an affable enough working-class stiff (soon, I fear, to be very stiff) who was previously the subject of John's haughty, classist disdain. The family's latest tableau of depravity is going to involve these two men. John is given instruments to mutilate the window-washer, or maybe worse.

And, well, isn't that the position the bourgeoisie holds with respect to the truly rich? Climbing his way up, John's more powerful than the window-washer--but all that power affords him is the role of (in this case, literal) hatchetman for the truly elite. He's still a plaything.

The Ribbon Rule by Mae Jimenez

Synopsis: In a dystopian society where becoming a teenager means having your mouth sewn shut, Rosa challenges the status quo.

Thoughts: There are some things I go into with open hostility which won me over; this story was one of them. Nothing against Jimenez, I should stress, but I'm intensely skeptical of post-Atwood dystopias. Even more so when our hero is an adolescent and we have capitalized terms like "the Bind" and "the Ribbon Rule." But this isn't a YA dystopian retread; Jimenez spends a lot of time on the body horror here, and of the practical ins and outs of having a mouth sewn shut. And they're repulsive.

There's some interesting political horror here as well. The Bind (the agents who enforce the system) and the seamsters/seamstresses are the aporia, the required exception, the act of unjustifiable violence which constitutes the entire system even while contradicting it. Both the system and its own resistance are bound together. Assume the Bind are genuine, and that their mission is based on their real ideology. Eliminating all speakers would be the ideal place on earth. They'd, you know, immanentize the eschaton or whatever. But this society would quickly break down because if nobody wanted to speak, there would be no sewers or authority figures, and the system would collapse with the demise of the last speakers.

At the same time, this exposes the typical resistance as just part of the problem. By speaking, Rosa guarantees the survival of this cruel, senseless system for at least another generation. The speakers and the silent are linked to each other, bound by a dialectic stronger than silk ribbons.

The Night Birds by Premee Mohamed

Synopsis: A social worker and two cops track down the itinerant family of an abused runaway. Then the Night Birds show up.

Thoughts: Good, straightforward horror. It's like drinking a really good beer at lunch while on a summer vacation: It satisfies your thirst, gives you just enough of a buzz, and has a bit of flavor beyond what you'd expect. This one is clean and crisp, and it clips along with good pacing. This feels like it could be an episode of a horror anthology show; it's neatly contained, easy to imagine, and visually striking. And, in a collection that's been full of well-done monsters (and even bird monsters), the Night Birds stand out.

Pages From a Diary by Steve Kilbey

Synopsis: Excerpts from the diary of a monster in the late 19th century.

Thoughts: I went into this story skeptical, too. I like poetry, but usually not in my horror anthologies. And period pieces about vampires (I'm assuming this is a vampire, although some of the details complicate things) are. . . not very interesting to me. This rises above that, though. It puts me in mind of Thomas Tessier's exemplary The Nightwalker, where the focus is less on the particulars of the folkloric monster and more on how it plays out in the deranged mind of a special serial killer. A more apposite example might be Basil Copper's Jack-the-Ripper epic "Black Blades Gleaming."

As poetry, it's quite good--it manages to a square a circle by maintaining coherence as "real" poetry (and not just "prose with funky line breaks"), and as a real narrative.

Broken Back Man by Lucie McKnight Hardy

Synopsis: A young bartender suffers a shock when the grotesque, broken man from his adolescent dreams appears in his pub.

Thoughts: There is a problem in "best of" collections that you'll have well-done, well-executed variants of familiar material pale in comparison to the more audacious experiments in style and content. This is kind of the situation for Hardy's story. This isn't a criticism at all of the tale, and I think it's good that there's ample diversity in the anthology because that shows off just how many ways there are to write great dark and upsetting content. Again, it's more that we're grading on a curve.

So what does this story do particularly well? It nails the pub setting, for starters. Hardy is also good at parceling out the shocks--the revelation of just what the book is that the broken back man has with him hits like a ton of bricks, or maybe a keg of beer falling from a high shelf. But, when I think of the story, it will be for the clever, cruel little ending which ties it all up nicely.

I Love the Very Flesh Off You by Robert Shearman

Synopsis: A couple attends the funeral of his wife's ex-husband, where the rivalry between her and the deceased's widow goes way too far.

Thoughts: I'm hooked on Shearman. His "Dismaying Creatures" was the highpoint of the "Day" half of Night/Day, and this is even better. Again, it's a black comedy of manners, with people tossing off outrageous statements and doing even more outrageous things. This is one of those stories--sort of like Stephen Graham Jones' story in Night--where I don't want to write too much about it because the fun is discovering it yourself. And you should. But here's one running gag: Throughout the story, the narrator refers to marital relations with his wife as "the sex thing," which is funny itself, but then later on they "make love" instead of doing "the sex thing". And it doesn't just seem to be a difference in terms of emotional tenderness--you get the sense that both acts are not only distinct but both may be at best orthogonal to any normal sexuality.

Read this story. It's like an episode of Arrested Development written by Thomas Harris. It's great.

Comments

Post a Comment