Chill Out! Cold Shocks (ed. Tim Sullivan)

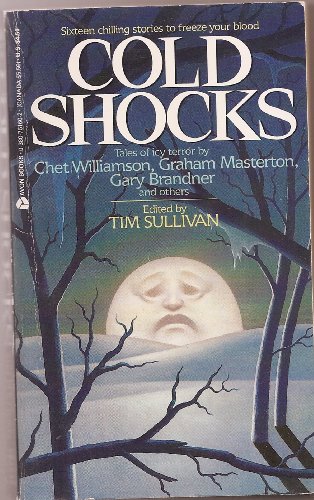

Here's another early-90s obscurity I've been curious about--Tim Sullivan's Cold Shocks. This is the companion volume to his Tropical Chills, which interests me less as it has 1) an ugly cover and 2) a lot of reprints that seem more like pulp SF than proper horror. These are all new stories, though, and it has an exciting lineup. And, while the moon on the cover looks more distressed than either scared or scary, I really like it. Each story has a bonus ranking by how cold it makes you feel; this isn't necessarily an indicator of quality one way or the other.

The Ice Children by Gary Brandner

Synopsis: An investigation of a mysterious encampment in the Alaskan wastes reveals an inhuman presence.

Chill Factor: 34 degrees Fahrenheit. It's not freezing, but the difference is academic.

Thoughts: One of the problems with the great 'paperbacks from hell' is that you had glorious and outrageous scenarios that were...poorly written, at best. At the extremes, this could turn into a delirium all its own, but after a while, you realize it's not worth slogging through mediocre prose just to get to some animal attack scenes you've already read better in Slugs and Lair.

Brandner, though--I was expecting greatness. I've heard The Howling is pretty good, and that books like Walkers and The Brain Eaters are sleaze classics. Going into this, though, the only Brandner I'd read was his erotic voodoo story "Aunt Edith" in that superlatively scorching anthology Hot Blood. "Aunt Edith" is only right at the demilitarized zone between "okay" and "actively good", but it does its thing with enough zest that I was hopeful

And then I hit the sterile turgidity of "bestseller-ese." I've never read an Arthur Hailey novel, but I've read parodies of that sort of thing. There's a sterility to it. It's "bestseller-ese." If I may introduce three of our dramatis personae:

"Vito Calli, slim and athletic in the blue thermal suit, raised a gloved hand in salute and grinned at him. Calli, a navy pilot, was the youngest member of the group. Each of them was checked out to operate the copter in an emergency, but Vito Calli had the confidence and experience necessary for flying into the icy unknown.

The dark, blunt-featured face of John Savitch, the geologist, betrayed no emotion. This land of ice and killing cold was his heritage, yet he alone of the four had to be persuaded to join the expedition. He smoothed the front of his green thermal suit and looked away.

Allison Denny, the photojournalist, could not disguise her trim figure, encased as it was by the bright yellow suit. Her calm intelligent gaze met Bettiger's, and it was he who blinked first."

Do you get the idea? And, as for the dialogue:

"Looks like we can't blame the Russians for this one," Calli said.

"Vito, don't you know the Cold War is over?" Allison said.

"Oh, excuse me. I haven't read the morning update on who are the good guys and who are bad."

Geez.

Maybe I'm doing Brandner a disservice, and this is an elaborate sendup of that kind of thing, with its big bestseller campaign and instant film adaptation, right down to the "gotcha!" ending. But I don't think so, and either way it's a waste of an amazing set-up. We have Alaskan Hills Have Eyes. How do you botch that? It should be impossible to screw up "Off Season, but it's in Alaska and also they're Inuit zombie mutant babies who were left to die of exposure and now they eat people." And, to give Brandner his due, the parts of the story that focus on the fear and the gore are effective. But it's all encased in this airless, clunky writing. That it isn't actively "bad" the way something like Eat Them Alive is bad doesn't even help. It reminds me of what Stephen King said about Cruising: It's a dead rat in a Lucite block.

First Kill by Chet Williamson

Synopsis: Deer hunters find themselves stalked by an eco-avenger.

Chill Factor: Morning after sun-up in the tree stand, relying on hand warmers and a thermos of coffee to keep warm while waiting for the deer.

Thoughts: Form meets function here, and if we're going into this one we're going to have to go into some spoiler territory. So if you're thinking of getting this book, skip this.

Williamson divides the story into alternating sections. Half is from the point of view of the unknown 'hunter' who is out to even the odds on behalf of the deer, and Peter Keats, who is gamely along for the hunt with his buddies even though he never has and never intends to shoot a deer.

Here's where Williamson successfully tricked me; he meta-gamed it. Indeed, you might say that he made me ("the hunter") into the hunted. I figured that the switch back and forth between "the hunter" and Keats was intentional, and that Keats was going to engage in partisan warfare on behalf of the deer he won't bring himself to shoot. Then, at the end, as the reader is gasping at the reveal that our likeable Keats is actually an eco-terror sniper, I would shake my head. "Called it," I'd say, and turn to the next story.

It doesn't work that way; it's much better. But I will have to get into the ending, so are you sure you want to know the rest?

Okay, then. Well, Keats is actually a deer-human hybrid, and. . . I'm kidding. No, Keats is a human, and he's not the killer. He comes upon the killer, who's just gutted his victim, they both grab their rifles, and Keats (to his surprise) is quicker on the draw.

I really like this, not just because I'm glad that Keats lived (he's doubtless going to have an uncomfortable conversation with the police after the story ends, but I'm sure he'll come out okay), but because it's a clever double-inversion. The basic set up of the story is a reversal: The hunter (the Pennsylvania deer hunters) become the hunted. But then Williamson doubles-down: The hunter of the hunters himself becomes the hunted, at the hands of Peter Keats. Of the three men present at the story's end, the only one who is alive (who "won the hunt") is the one who went into the woods that morning never intending to hunt or kill anybody or anything.

It's great.

Colder Than Hell by Edward Bryant

Synopsis: Tensions rise when a Wyoming farmer and his wife are trapped by a blizzard.

Chill Factor: Brass-Monkey Orchiectomy levels.

Thoughts: The first story here which actually captures what it's like to be in the cold. This is a dark, brooding piece with that mines a good vein of chilly cruelty. It also does a good job of feeling like a period piece (could be anywhere from the mid 1800s through to the 1930s) without being rooted in too much detail; technically speaking, this story could happen today. Minor spoilers follow.

It feels like an Alfred Hitchcock Presents kind of story, with the exception of the ending--Bryant doesn't go for the sort of big ironic comeuppance scenario you'd see in AHP or an EC Comic; instead, we get something more similar to the 'fade to black' ending of No Country for Old Men. I like that ending, and I like this ending, but I could imagine other people not digging it.

The Kikituk by Michael Armstrong

Synopsis: Simeon, a young man with fetal alcohol syndrome, visits Anchorage and his kinda, sorta stepfather (the ex-cop who rescued him as an infant). Simeon's not alone, though: He has a magical power with him--and a score to settle.

Chill Factor: Sitting inside with hot cocoa watching the wind blow. This is much more a story set in Alaska than a story about the cold as such, although that's not a problem.

Thoughts: Probably the best story in the book, thanks to Armstrong's familiarity with Alaska. It's very well written, and Armstrong incorporates pertinent social issues--FAS, Native life in Alaska, child abuse in a way that's intelligent and sensitive without being cloying or preachy.

The horror elements are great, too, with maybe the best "special effects" and gore here. We have shrieking, red-eyed, needle-toothed monster heads shooting out of coat sleeves and then opening their mouths to shoot forward more monster heads in a reductio ad absurdum of the xenomorph design. And there's a more prosaic element to Simeon's revenge, a bit of EC Comics poetic justice that's pretty ghastly.

There's some fat in the middle involving the investigation of an early victim which bogs things down and doesn't make much sense, although it did at least remind me of any number of 'Indian magic and bloody airport bathroom' scenarios from Ramsey Campbell's uneven but underrated HWA anthology Deathport.

The Christmas Escape by Dean Wesley Smith

Synopsis: Every Christmas Eve, the ghost of a former resident recreates her ill-fated escape from a nursing home.

Chill Factor: A few cups of cold water thrown in a warm bathtub.

Thoughts: I really didn't like this one, in part because of whoever wrote the back cover copy to the book. The ghoulish come-ons accurately describe Williamson's story ("Join a hunter on a horrifying winterkill when a desire for human blood brings out the beast in a man") and Brandner's ("Journey to an Arctic hell where a tribe of abandoned mutants thirst for revenge"). The obvious third story for the blurb, to my mind, would have been "The Kikituk", but instead Smith's story gets touted as "[S]pend a frigid Christmas Evil with an old woman in a haunted home for the elderly." "Christmas Evil" suggests a threat, right? Or, at least, conflict? And that isn't present here.

It isn't a bad story, or even mediocre. It's just generic--a standard ghost story, with a little bit of pathos and a little bit of spookiness. But there's never any threat. I originally misread the final line as implying the ghost led the narrator out to freeze to death, which did give me a sick jolt. But, alas, no.

It does get one bonus point for being a Christmas ghost story which references, in a throwaway line, a nurse helping "Mr. James" (M.R. James, get it?) eat. But even that just reminds me of spookier ghost stories to read instead.

A Winter Memory by Michael D. Toman

Synopsis: A shy young man tries to kiss his girlfriend.

Chill Factor: Lukewarm, flat, caffeine-free Diet Coke.

Thoughts: Brandner's story has worse writing, but this story is worse as a story. The synopsis isn't everything (there's a surprise, and it's not the one you might be guessing from reading that synopsis), but it's much too much of the story. There's one good part, in the middle, but that's not enough to sustain the story

It almost gets some points back from veering into a micro-genre of horror story I'm very fond of--I can't tell you what it is, but I'll say that both Bruce Jones and Robert McCammon have written similar stories. However, both of those writers set up their eventual revelation much better than Toman does, so what's a satisfying twist in their hands is a "wait, what the hell??" in Toman's.

The Sixth Man by Graham Masterton

Synopsis: An oil company geologist discovers evidence of a mysterious sixth member of the doomed Amundsen polar expedition.

Chill Factor: Freezing!

Thoughts: Masterton has written a number of these horrific revisionist history pieces. It's a solid story, although not as fantastically tasteless or off the wall as some of his other work, but I think this is a good counter-weight to "The Ice Children." Both are adventure/horror hybrids with plenty of helicopters and arctic outposts and investigations into people in places where they rightly don't belong. But, while Brandner's story bogs down in potboiler territory, Masterton's zips along.

The threat here is also clever, although it took me a little while to get it. "Third Man Syndrome" is a well-documented, but still mysterious, phenomenon in which people in extreme survival conditions report feeling the presence of a benevolent phantom guide or person. Whether you believe it's a guardian angel or an extreme psychological coping mechanism (or maybe a little bit of both), it's comforting.

What I didn't know (but learned just now brushing up on Third Man Syndrome for this post) was that it was made famous by Sir Ernest Shackleton in his account of his celebrated Antarctic expedition; Masterton was no doubt aware of this and for all I know it's what inspired the whole story. It's a neat inversion here--instead of the extra man being a guardian angel (real or imagined), it's the avatar of death and despair. It's those sorts of touches of intelligence and class that always elevate Masterton's work.

The Ice Downstream by Melanie Tem

Synopsis: Torey and her father live in a world of ice--physical and emotional--ever since her little brother died.

Chill Factor: Slurpee-based brain freeze: Very cold, and goes right to your head.

Thoughts: This story uses cold and freezing as a metaphor for grief--both the way it makes you feel, and the way it can keep you locked "frozen" in the past instead of thawing for the present.

It falls into the trap that a lot of allegory does, which is that everything makes "too much sense" (that is, it's clear what all the parts are supposed to mean, so the bizarre happenings are readily explainable with reference to the metaphor). This can be to the detriment of a more symbolic story (and especially a horror story), where the unknown and unexpected are part of the appeal. However, I found this story moving and effective all the same

Morning Light by Barry N. Malzberg

Synopsis: A bizarre series of encounters and interviews with figures of modern poetry.

Chill Factor: A cup of hot tea.

Thoughts: There are some names that always perk me up when I see them in an anthology table of contents from this timeframe: Steve Rasnic and Melanie Tem, Elizabeth Massie, Ray Garton, David B. Silva.

Then, there are names which make me go, okay, this should be interesting. Barry N. Malzberg is an example. He's fundamentally talented and creative , and all has written stuff which ranges from "this is unimaginably brilliant" to, uh, not.

On paper, "The Atrocity Exhibition but with post-war poets" is something tailor-made for me. However, I found this much too self-satisfied. For all his satires and weirdness, Ballard's work is rarely if ever smug; if it were, it would be unbearably pretentious. Malzberg maybe dodges this at the end, when Robert Lowell rebukes his narrator in a "magnificent if somewhat patronizing speech", but that's only part of the problem.

The other part is that, although this work acts as though it is grappling with the horrors of the 20th century, it isn't. It says it is, but it isn't in any meaningful way, and so its project rings hollow.

I will absolutely revisit this story--it's too interesting and layered and ambitious not to--but I don't particularly like it.

Bring Me the Head of Timothy Leary by Nancy Holder

Synopsis: An acidhead turned documentarian and the flight attendant he'd been flirting with are the only two survivors of a plane crash somewhere cold and dark.

Chill Factor: Ice pack out of the freezer.

Thoughts: I was a little down on the last two Holder stories I encountered, but this one is great.

Part of why it works is the main character occupies an interesting area between "Annoying Guy Who Deserves What Happens To Him" and "Likable Enough Guy Who Doesn't Deserve This." Part of it is archetype: Boomer flower child turned Boomer establishment man offers a lot of territory to hate. This particular guy is a bit grating, too, with his constant namedrops and self-indulgence on the airplane.

But he has an interesting life, and deserves better than to wind up on ice in a plane crash after getting a big break. The flight attendant is good too; I only put her later because Holder doesn't (in fact, for the story to work, can't) give more insight into her thoughts. The dialogue is interesting and entertaining, and the constant threat of the cold and of drifting off to sleep, never to wake up again, invests you in that dialogue. It isn't just small talk, or character development, but a matter of survival. And, before things get repetitive, Holder blindsides us with an ending that's 1) unexpected, 2) very fairly set up (kind of like the Bob Booth story "The Play's The Thing", it's laying groundwork long before you realize it), 3) horrifying, and 4) pretty damn funny.

This would make a heck of a Grand Guignol play.

The Bus by Gregory Frost

Synopsis: Driskel once had a good life, but now he's sleeping on the frozen Philadelphia streets. On one harsh winter day, he decides to investigate the massive, mysterious bus parked on his street. . .

Chill Factor: High wind chill, but not so bad under a little cover.

Thoughts: There was no way they wouldn't let a guy named Frost in the 'cold horror' anthology, right? Anyway, spoilers below.

I fundamentally like this story; it operates in the same surreal dreamworld as stories like Melanie Tem's "Fry Day" and Lawrence Watt-Evans' "Parade" (even if it's not as good as either of those stories). At first I was jarred by the transition from stark realism to "The Wild Party"-style magical realism, but both parts are good.

However, I think Frost's story misunderstands its central metaphor. The idea here is that non-stop party bus of rich people is always on the move, literally fueled by the most outcast and vulnerable members of our society (who get a brief taste of creature comforts and acceptance in return).

This does work well in the narrator's case--he was once a part of this class, although at the lower end; an upper middle class professional, I imagine. Then something went wrong, and the society which served him and he served jettisoned him to the street. His time on The Bus, then, is essentially a literalized speed run of his life arc. This ties in nicely with various Marxist ideas of precarity and surplus labor and a subproletariat--nobody is ever irreplaceable, and even your ability to sell your labor becomes uncertain (which will only increase the other side's leverage).

But...if you're doing a critique of capitalism in horror story format, and dramatizing the exploitation of labor in capitalism by having the machine which benefits the rich grind up the laboring class, you can't have the fuel be the explicitly unemployed! When I say that Driskel or his acquaintances aren't contributing to society, I'm not condemning them or suggesting they deserve what's happened to them; I'm simply stating that they're not engaged in any sort of production. If you want the metaphor to work, Driskel et al. aren't the power source, they're the excess, the byproduct that the machine produces and excretes and tosses onto the street for society to deal with (or not).

There are some unpleasant implications there--if you go down the route of suggesting that the homeless are a "waste product" which leads to some conclusions Frost certainly wouldn't want the story to reach (per the author's note, this story was inspired by Reagan-era deinstitutionalization policies and the lack of support for the homeless and the mentally ill). But, hey, I didn't pick the metaphor!

Adleparmeun by Steve Rasnic Tem

Synopsis: Joseph was the only survivor of his village. Now he's a social worker in Denver, but he feels equally ostracized from modern urban society and his Inuit heritage. Then the two worlds collide. . .

Chill Factor: Walk-in Freezer.

Thoughts: As usual, a Steve Rasnic Tem story which demands, and rewards, careful attention and re-reading. The first time through, I assumed that the new Ice Age which descended upon Denver (and perhaps everywhere) was a replication of his past in the village: In both cases, he's an outsider in a failing community in the Arctic waste and doom shows up. 20th century Denver is presumably better equipped to weather the storm than the isolated Inuit village of Joseph's childhood--but I thought that the "failure" was less logistical and more moral (as suggested by the social malaise Joseph sees in his job).

That didn't really satisfy me, and on a second reading I think I came closer to the point: The snowpocalypse adult Joseph faces isn't something that's affecting everyone else; it's his personal trip to Adleparmeun, the frozen Inuit hell. The key here (which I missed the first time--admittedly, I was distracted by cars turning into bears and apartment buildings frozen in blocks of ice) is that it's a battle between Joseph the man and Joseph's own soul (the soul of a shaman?) which he's abandoned. The battle between his wanting to be part of the modern world and his ties to his heritage is what's happening here. I know essentially nothing about Inuit mythology other than, honestly, what I've picked up in this book, so I don't know if Joseph's attempts to steal his name back from his soul at the end is directly rooted in folklore or if it's SRT's own invention. However, I think it symbolizes Joseph's efforts to have his own name--be his own person--apart from the supernatural and cultural obligations his background placed on him. He's trying to be just a man, not be a shaman or a mystically ordained hero figure. But his soul won't let him, which is why we end the story in an odd state of both triumph and despair.

This ambiguity matches the ambivalence that runs through the piece--Joseph's ambivalence (not indifference, but ambivalence in the psychological sense of being torn between two extreme feelings) towards his clients ("he was torn between screaming at them for their weaknesses and excusing them wholesale") and the instability of the shaman ("[h]is grandfather said there were two kinds of madness, the madness that might make you a shaman, a medicine man for your people, and the madness that made you a danger to the tribe").

I'm not certain I have it "right"--there's a lot to chew on here, and I'm at a disadvantage with my unfamiliarity with the subject matter--but it's thought-provoking, intelligent, and has some spectacular fantasy imagery as well.

Close to the Earth by Gregory Nicoll

Synopsis: A business traveler stops off at a small-town diner for some coffee, food, and, if he's lucky, female companionship.

Chill Factor: Delivery food that's gone cold and soggy. This isn't a reflection on the story's quality--it just doesn't really sell "the cold."

Thoughts: I thought at first this was going to be a folk horror story in the "Children of Noah"/"Children of the Corn" knock-off mode. What's that, attractive waitress? The corn crop went bad? And the folk around here like to keep to themselves?

I'd say that our narrator's in the running for sex (if he's lucky), or the promise of it (if he's not), followed by an all-town celebration to meet and greet the new fertilizer. . .

And then the waitress brings him his eggs, and the story swerves. I won't say where it winds up, but it's another subgenre of story I very much enjoy.

My one major criticism has to do with the last half-page. Although I appreciate that it doesn't end on the typical "and then the bad thing happened, or is about to" note, this tacks too far in the other direction. So let's split the difference, lean into the ambiguity, and keep it a little darker. Just end after our man comes around back and gets a good look at . . . well, I won't tell you what it is. I will put your mind on the right track, though, by saying this would have been a helluva story for Bruce Jones' great, sleazy 1980s horror comic Twisted Tales.

Snowbanks by Tim Sullivan

Synopsis: After his brother's death, Jerry finds himself wanting to be alone. The massive snowbanks in his neighborhood provide a perfect opportunity.

Chill Factor: Getting your tongue stuck to the flagpole.

Thoughts: Sort of a companion piece to "The Ice Downstream;" both of them are dark fantasies from the point of view of a child dealing with the loss of their sibling. It's sad, creepy, and hopeful all at once, and Sullivan captures the child's-eye view of the world well. It exists in the same hazy netherworld between fairy tale and 'realistic' horror story that the stories in Al Sarrantonio's great collection Toybox do (it's actually quite similar in some respects to Sarrantonio's "Snow"), and you could imagine this one in one of the Bruce Coville-edited YA horror anthologies from the 1990s. The one mark against it is that the descriptions of little Jerry digging his tunnels are about as entertaining as shoveling snow.

St. Jackaclaws by A. R. Morlan

Synopsis: A boy's theory about "St. Jackaclaws"--the Wolpertinger-esque beast that's the foundation of all holidays-- takes on a grisly life of its own.

Chill Factor: Late October.

Thoughts: A year or two after Cold Shocks came out, the world would thrill to the Christmas/Halloween mashup of The Nightmare Before Christmas. Morlan got there first, though, and doesn't just combine Halloween and Christmas--she posits a gestalt holiday entity responsible for everything from Valentine's Day to Thanksgiving. It's a fun idea, and so is the mid-century Upper Peninsula milieu of the story. It is a lot of fun to read.

I do think it's a slightly missed opportunity--the 'horror' part of this story is solid enough, but seems a little limited. I would have leaned into the possibility of creating the ultimate holiday slasher, in which troubled young Kent hacks up townsfolk to collect each part of St. Jackaclaws.

The Pavilion of Frozen Women by S. P. Somtow

Synopsis: A Native American journalist covering a Japanese festival is thrust into a whirlwind of murder, art, sex, and magic.

Chill Factor: A cold day of skiing in Hokkaido.

Thoughts: "The Pavilion of Frozen Women? I said, 'Hey, buddy, I think that's where my wife came from!' Nah, but anyway, folks..."

You know what? It's my blog, and I don't always have to leave stuff on the cutting room floor!

Anyway, I've long been curious about this story; I knew Somtow's collection of the same name got a bunch of award nominations back in the day, and I've always mused on what a pavilion of frozen women entailed. Was it science-fictional? Was it fantastical? Was it like some depraved art thing?

Turns out, it is some sort of depraved art piece. But here, that's only part of the story. There's also shamanic bear-man magic! Complaints about the high cost of living in Japan! In-depth consideration and contrast of racial dynamics in Japan and the United States, with a particular focus on Native Americans and the indigenous Ainu people!

This story is all over the place, and while I was reading it I wasn't sure whether I liked it, but it's a strong closer--certainly the most colorful story of the book. What this story reminds me the most of, funnily enough, is William Gibson. The dizzying trip through Hokkaido's crime scenes, winter festivals, and swanky receptions, jammed with clamor and conspiracy, feels like a cyberpunk tale. At first, I wondered if that's just because we're in Hokkaido, and East Asian influences abound in so much cyberpunk, but I don't think that's all it is. This is a story worth reading, because I guarantee it will coax a reaction out of you--even if that reaction is revulsion. You may hate this story, either because of the content or the form, but you will have a strong response. And that--not the petrified prose of Brandner's opener--is what literature is all about.

Comments

Post a Comment