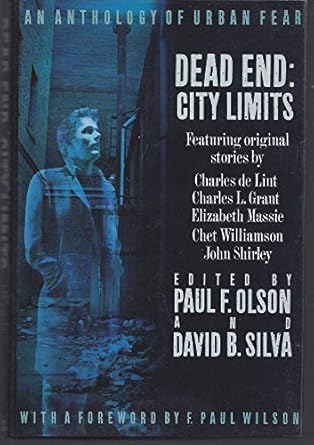

City Blocks, City Shocks: Dead End: City Limits (ed. Paul F. Olson & David B. Silva)

Here was a treat I stumbled upon the other day: A horror anthology I'd never heard of, with a fun theme (urban horror), a strong line-up of contributors, and right in my late 80s/early 90s sweet-spot for horror.

I often skip the introductions to collections, but given that the introduction to the other Olson and Silva anthology I've encountered (Post Mortem: Tales of Ghostly Horror) was a literate, meta-textual ghost story about books of ghost stories, I thought this would be required reading. It is--both F. Paul Wilson's enjoyable thesis statement for the book, and Olson and Silva's exegesis both of the book's themes and of its conception.

This isn't quite a "shared world" anthology--there isn't a single fictional place like the Greystone Bay of Charlie Grant's anthologies. We have stories here that take place in New York, Washington DC, Los Angeles, and New Orleans, as well as ones that take place in a more abstract, conceptual 'city.' However, all of these cities are really just part of what Wilson, Olson, and Silva all refer to as "The City." As Wilson writes, "The City. . .embraces the best and worst of all cities," and while the stories may "claim to be set" in this or that known metropolis, they're just facets of The City.

This is a horror anthology, so the emphasis is more on the best than the worst. Olson's vision for The City is one with a laundry list of urban ills: Violent crime, political and police corruption, income inequality, ethnic Balkanization fueling racial tensions, and crumbling infrastructure. At the same time, Olson and Silva write, they were partial in their editing to those stories that allow for some hope. It's a compelling hook for an anthology.

I want to spend some time at the outset getting political--not in the way you're dreading at Thanksgiving dinner two days from now, but at an abstract level of theory--and I think it is warranted. Cities are political--they involve the organization and coordination of communal human life and activity, and that's basically what politics is.

I think horror stories about the city qua city are fundamentally reactionary, and I want to clarify what I mean by that. I'm not saying that these stories are inherently one flavor or another of right-wing politics; still less am I saying that these stories are "problematic." I'm talking about a type of reactionism that exists upstream of any particular political ideology, and that fears and resists change and wants to protect the community. These are natural tendencies in human societies, and you probably need some level of these impulses to identify and preserve that which needs preservation.

You can draw obvious parallels to right-wing politics past and present, but note that it also crops up in left-wing politics: There are strong anti-urban elements in Maoist thought and its offspring, for example. Just ask Pol Pot.

Why be afraid of the city? Several reasons: Cities are unnatural: They're cut off from the natural world and are their own artificial landscapes of concrete and glass and smog. They're dirty and unhealthy. The economic activity of cities follows an 'unnatural' trajectory as well--you move away from agriculture and crafts to, first, industrialization (economic activity of and by technology), and then post-industrial service and finance economies, the latter in particular only tenuously tethered to reality. Cities present you with the Other: They're heterogenous and bring you into contact with people who aren't the same race as you, aren't the same class as you, who don't speak the same language, or who don't share your values. Most importantly, and somewhat subsuming all of the above, cities are where change happens, and where it happens fast.

That's the lens we're going to look at several of these stories through, today. Don't worry, we're still going to chat about blood and guts, too!

I think it is unfortunate that Silva and Olson's dream of three anthologies didn't come to fruition. The project originally would have included books about rural and suburban horror along with this one, because I suspect it would support another two theories:

I think that horror stories about the rural qua rural are fundamentally progressive, which has nothing to do with their or their authors' commitments to left-wing politics. I mean it as the opposite drive to the conservative or reactionary element of society If the City is where progress has gone too far, the Rural is where the Old Ways still remain, where isolation and small numbers makes it easier for the strong to tyrannize the weak, where technology and economic development haven't overcome the material privations of life, and where superstition and insularity paint a target on the back of everyone who's different. Again, this progressivism isn't necessarily liberal--The Wicker Man, for example, is a work in which a somewhat priggish conservative and his Christianity are the good guys: Sergeant Howie is a stick in the mud, but he's not the one abducting policemen for semi-consensual stud purposes followed by wholly non-consensual immolation (I'm grateful to Howard David Ingham's We Don't Go Back for this observation).

I also suspect the book about the suburbs would have operated at a similar level, maybe even upstream from reactionism and progressivism, at the level of a death drive. Suburbia is triumphalism and self-satisfaction. It is modernity and sees nothing wrong with its own values. Suburbia stands in (certainly in post-war American culture onward) as the hegemonic culture, so becomes a useful tilting horse for every other sort of social or political tendency.

Enough chit-chat. Let's get spooky!

Parade by Lawrence-Watt Evans

Synopsis: A group of coworkers find their lunch plans impeded by a mysterious, endless parade.

Thoughts: This is a strong opening, and something of a statement of purpose for the collection (as though the dual introductions weren't enough). Hell is other people--not just other individuals, but other people as a collectivity. This is an unabashed allegory that stays grounded by beginning with realistic and relatable woes (unexpected crowds impeding your plans) and ratcheting up into mind-shattering, borderline-apocalyptic madness. In this regard it reminds me of Ramsey Campbell's work, and in particular "Going Under". However, the crowd in that story is really more a benign (if often rude) entity that becomes a focal point for Campbell's protagonist's desperation and madness. Here, the crowd--society--is out to get you. Even though that's what you've wanted, all along. Isn't it?

The Looking Glass Hand by Melissa Mia Hall

Synopsis: 12 year old Robin has to manage his siblings after Mom disappears with her new boyfriend.

Thoughts: "Mom hasn't come home and Dad never did." That's a great first sentence. Look at what it does--it sets up conflict, it tells us something about the relative age of our narrator, and it gives us some hints about the milieu this story will take place in. Even so, I wasn't prepared for the claustrophobic, terrifying, and plausible (hell, not plausible. REAL.) world of poverty and neglect and desperation Hall shoves us into. It reminds me of Kids, although Hall's story has much more in the way of empathy than mere exploitation or provocation.

Hall wisely shies away from 'horror' content In fact, the one piece of the story that doesn't work for me is the closest it comes to flirting with the fantastic. That's the titular looking glass hand, a family heirloom with alleged fortune telling powers. It doesn't go anywhere, other than to subvert the notions of a fairy tale ending: There's no family magic, no hope, it's all bullshit and you're screwed.

Unless...unless the looking glass hand can tell the future, and the blank nothingness it returns when Robin looks at it is indeed his future, stamped with the supernatural seal of authenticity. Not that it matters much for poor Robin by the end.

I love this era of horror so much.

Make a Wish Upon the Moon by Charles L. Grant

Synopsis: A neighborhood's decline coincides with the arrival of a mysterious dancing man.

Thoughts: I'm not sure anything can top the story Grant tells in the introduction, which is about him and Kathryn Ptacek fighting off muggers in Times Square. But "Make a Wish Upon the Moon" has plenty of charm on its own merits. The story flows easily, and at first it feels like a continuation of the (generally non-speculative) stories Ray Bradbury set in cities, stories like "The Wonderful Ice Cream Suit" and "I See You Never" and "Touched With Fire". However, the story slides into fantasy territory.

It's great stuff--it retains the gritty feeling of urban decay from the first two stories, but with the subtle, beautiful twists you'd expect from a Grant story.

This is the first story in the collection to give us that bit of hope mentioned in the introduction, even if it's very small. However, I think the gentleness of the story might blind us to the bitterness of the ending. The bit of hope our protagonist has isn't for The City as a whole--it's for him and his neighborhood, and he'll only be able to get it at the expense of another neighborhood. Behind all the beauty of 'dancing down the moon' lurks a zero-sum urban future of fragmented warring communities.

Ash by John Shirley

Synopsis: An unemployed man tries his hand at armed robbery, and stumbles into a hellish city of his own making.

Thoughts: Best of the book. It had been a little bit since I read a Shirley story, and I forgot just how potent his stuff is. We begin normal enough, with a Donald Westlake-ish tale of a white collar guy dabbling in crime. Like all good crime stories, he thinks he's smarter than he actually is. That's just the beginning, though. After the robbery goes wrong (of course), things really take off. When we got to the children ripping out their eyes to play jacks with them on the sidewalk, I got excited. And by the time a cop car full of twitching, sparking mannequins had finished driving into a crowd on the sidewalk, I knew it was true: I was in the middle of another John Shirley Certified Freaky Banger.

I'll leave you to discover the rest of his pyrotechnics for yourself, because I want to talk about the social point Shirley makes. At the end, Ash (our protagonist) winds up in a hotel room, except it's already filled with people: Family members of the armored car guard Ash shot during the robbery. And soon, dozens and dozens more people crowd into the tiny room, each of them a person in some way negatively impacted by Ash's selfishness and crimes. We're all connected, is the point.

This isn't Shirley's only work that hinges on overcrowding and the sheer density of people, but whereas his award-winning story "Cram" makes it a bizarre, transcendent experience (almost like something from Junji Ito or Shintaro Kago), this is serving a social and political point. And, it reminds me of two other works, one of which is generally in line with Shirley's humane sympathies here, and the other of which is not.

The one which isn't is Jean Raspail's notorious, xenophobic The Camp of the Saints, in which the Third-World masses overrun the Western world. Raspail's book is as reactionary as it gets, and is fixated on images of crowds and crowding. One might say that part of Raspail's thesis is, "Look! What you bleeding hearts think of as 'humanity' is a filthy, physical being which will take up your space; engaging with the horde will render the whole earth a pigsty." Reactionary, zero-sum politics.

The other story is Steve Rasnic Tem's "The Poor." "The Poor" is a parable about a man who works at an agency ostensibly in service of the poor, but he is unable to do anything to help them. He himself becomes fixated with the fears that he himself may soon join their ranks, and that they are going to take everything from him. His well-intentioned liberalism gives way to paranoia, and then violence, even as they encroach closer and closer into his life.

Tem's story is more humane than Raspail's book (really, what isn't?). Although the impoverished masses are again menacing, the story keeps us at a remove from the protagonist and his mind. In effect, we have a cautionary tale about reactionary impulses: The protagonist responds to the failure of society to address poverty, etc. not with compassion, or with renewed zeal to fix the system but with fear that the impoverished, cut off from social aid, will revolt and come for his own resources. And this zero-sum thinking leads him to madness and isolation.

This brings us back to Shirley. "Ash"'s conclusion is in some ways an inversion of Raspail's terror at the masses. In Camp, the problem is that the do-gooders don't realize their abstract principles of humanity will lead them into contact with the real thing. In "Ash," Ash's problem (and, by extension, ours) is that we don't realize the seemingly meaningless things we do have real consequences to real people in the real world. The throngs of people in Ash's hotel room at the end are objects of abject horror, but not because they are people of no worth. It's the opposite--they are people we recognize as having worth, and the horror is being confronted with the real people we never realized we had an obligation to, but have harmed. And this makes "Ash" not only the best story in the book, but maybe the most rigorously moral.

City Hunger by Chet Williamson

Synopsis: A man becomes obsessed with murder during an unpleasant business trip to New York City.

Thoughts: Pity Chet Williamson, who drew the short straw in following "Ash" and its hallucinatory freakout. Not just "Ash," either. Olson and Silva frontloaded four of the six best stories in the collection into the first four (the other two are Tem's and Brite's).

Thing is, this is a good story; the more I think about it, the more I like it. But, it did suffer on my first reading from having four hard acts to follow. And, while interesting, "City Hunger" doesn't have a super-original setup.

Williamson himself mentions in his introduction that it's a variant on Poe's "The Imp of the Perverse."

What things are original? The scene with the narrator in his hotel room, hiding from the giant blood red eye or mouth or whatever it is of The City is great (it's stuck with me for days now). And, I like the idea that once you've committed murder, you join a silent brotherhood of killers, all of whom can recognize one another (call it 'slaydar'?).

In terms of the reactionary theme--we have that here in abundance. This story is about the corruption and infection of The City: The narrator arrives an average man, and is thrust into contact with The City's violence and lowlives. He arrives a businessman and leaves having more in common with the human jackals disemboweling a victim in a train station men's room. And that's not the worst of it--he's going to carry the taint back with him to his home, infected with "a red, aching, unquenchable thirst, unappeasable hunger."

The White Man by Thomas F. Monteleone

Synopsis: An upwardly-mobile drug dealer and an aging pawnbroker investigate a boogeyman.

Thoughts: Monteleone's best work, in my opinion, is when it's clean and straight-forward. I've already written on here about my love of his stories like "Identity Crisis" and "The Cutty-Black Sow." Monteleone's worst work is when it's not. Then, it comes off as a bad Harlan Ellison imitation. That's true both of his fiction, like this story, and of his non-fiction (like his old Cemetery Dance columns).

That's the problem with this story--it's trying very hard to be cool and hip, and sort of Ellison-y, but there's a different between effort and effortlessness. It doesn't help that the "elemental supernatural force of The City" isn't a novel theme, although the notion that the river of evil under the city isn't slime like in Ghostbusters 2, but cocaine, is intriguing.

There's a kernel in this story that I am interested in: The idea of a savvy, black, new-money drug dealer from the inner city having to take care of a white Jewish-American kid as they try to i) find the latter's parents and ii) deal with a boogeyman has a lot of ways it could go. But, Monteleone wraps it up all too quickly.

Changing Neighborhood by Lois Tilton

Synopsis: An aging Polish couple and their new Vietnamese neighbors face neighborhood threats both real and supernatural.

Thoughts: The threat facing Mr. Dinh's family is real, and well-documented: In the late 70s and early 80s, there were waves of mysterious sleep deaths among apparently healthy Southeast Asians in the United States (many of them refugees from the Vietnam War and its fallout). Of course, the culprit isn't evil spirits--it's cardiac failure largely due to certain hereditary dispositions. This goes some way to explaining the ethnic specificity of the phenomenon, but there's another wrinkle.

Like in the story, some of these refugees did hold cultural beliefs about evil night visitors (similar to other cultures' mythologies around sleep paralysis), and were cut off from the socio-spiritual support frameworks that sustained them back home. It may be exaggerating to say that they were "scared to death," but it isn't hard to imagine that, if you woke up while experiencing some sort of sleep paralysis, and were already genetically predisposed to arrythmia, the additional fear and stress of facing what you might believe to be an evil spirit could push you over the edge. Of note: This phenomenon inspired Wes Craven to write A Nightmare on Elm Street.

What about this story? It's straightforward, a sort of horror-flavored Gran Torino. I think this is one of the most optimistic stories in the book: Mr. Dinh and his family have fled their home to a place where they feel they don't belong (and, sadly, where some of their new neighbors are more than happy to echo that sentiment). They feel that they've betrayed their homeland and its traditions, and now that they're in The City and cut off from their support networks, they're going to be punished (in a sense) by evil. Happily, they've got good neighbors in the Malek family, who fend off the threat in the most American way possible, and demonstrate the opportunities The City holds for new alliances, cutting across culture and race. Maybe the shadow is only gone for tonight, not tomorrow. But for tonight, that's enough.

Open Hearts by Stephen Gresham

Synopsis: A motley group of telemarketers find their office besieged by two threats: A blizzard, and The Bleeder.

Thoughts: It's always an unpleasant surprise when you come to a story in a professionally written, edited and published book that's...bad.

Some of this may be our narrator, whose street-smart patter leads through the story (such as it is). It's full of cliches and laziness, which is unfortunate because we have a multi-ethnic cast of varyingly disabled and disadvantaged telemarketers. I say unfortunate because, instead of either doing some deep and interesting character work and looking at these people's lives, or else leaning into the possibilities for giddy bad taste and swinging for the fences, Gresham's story relies on stereotypes. It's not "The Horror at Red Hook" or anything; it's just tepidly offensive.

The Rio Bravo set up is too strong to completely bungle, and Gresham pulls together a little bit of tension towards the end. But even that evaporates. Instead, go read Nancy Collins' "Easy's Last Stand," which is a better variant of similar material.

The Injuries That They Themselves Procure Must Be Their Schoolmasters by William Relling, Jr.

Synopsis: An English teacher and two unruly students get locked into a vicious cycle of revenge.

Thoughts: Almost great. Relling's story follows the Blackboard Jungle/Class of 1984 blueprint, with a militarized inner-city school (although, aside from the two problem students, this school seems to be doing okay).

It's nothing original, but Relling keeps the grim story moving. I think the use of a diary format helps this one. By its nature it takes place over a period of time and this lets Relling jump the gaps when nothing is going on and keep the pace up.

So why is it only almost great? It's a matter of the last few lines. The protagonist's initial revenge is a great, nasty, and clever bit of writing, and the idea that he gets away with it works with the skewed, "our society but just a little bit worse" vibe of the story. But the last couple lines take it from a good exploitation piece into a dumb Theatre of Blood knock-off.

Tallulah by Charles de Lint

Synopsis: A young writer reminisces about his relationship with a beautiful young drifter named Tallulah.

Thoughts: This is similar to Grant's tale, in that it's really a fantasy about urban decay and less of a 'horror' story. I appreciated the shift to a gentler tone after the grimness of Relling's story. However, I think the relative lack of horror is to the story's detriment.

The bulk of this story--sensitive young creative type falls in love with a mysterious supernatural girl--is something I know I've read before, and I haven't found it compelling there, either. It's not that it's bad--de Lint is a beautiful writer--but it's not compelling.

What is compelling is the concept of Tallulah functioning like a portrait of Dorian Gray, changing to reflect the character of The City. It's such a cool idea, and you can imagine her transforming from beautiful to ugly in a second, like Eva Galli in Ghost Story. This is also a more refined version of the "shared accountability" point from "Ash": The City is as beautiful or as horrible as we make it. Unfortunately, this story ends before we get a chance to investigate any of this in detail.

Spare Change by David Bischoff

Synopsis: Schizophrenic panhandler "Fruit Nuke" Ted finds his purpose in life: Exterminating Washington DC's drug dealers.

Thoughts: This is a funny, scary, edgy little story. There isn't a lot to it, really, but there are fun little grace notes like Ted's sacrifice to the Dark God of the City (it isn't blood, it's booze).

The ending, though...I don't buy it. The more subversive way would have been to lean into the conspiratorial zeitgeist and have him go gunning for the CIA or whatever. Bischoff lived in DC so maybe there's something I'm missing, but I don't think white-shoe DC law firms were in the business of representing drug dealers. At least, unincorporated drug dealers.

The City Never Sleeps by Gene O'Neill

Synopsis: A yuppie finds the familiar elements of the City vanishing, one by one. And he's the only one who notices.

Thoughts: This is a neatly-packaged Twilight Zone-style story; in fact, it's very similar to Richard Matheson's tale "Disappearing Act", which became a TZ episode.

What I find most interesting about this one relates to the "urban horror is reactionary" theme. This story is similar to Williamson's in that they conclude with the protagonist trying to escape the City to their home, but they bring the contagion of The City with them. O'Neill's tale makes this more explicit, however.

Our protagonist heads home to his mother and briefly has respite from the change and madness. But The City comes to take that away, too.

Lock Her Room by Elizabeth Massie

Synopsis: Johnny is on the third day of his initiation in his blighted school's locker room/oubliette. Luckily, he isn't alone.

Thoughts: We're back to the blackboard jungle, although this one is in much worse shape than the school in Relling's story. However, this is another story with hope at the end.

I don't think I'm reaching much to see a Christian allegory here--the girl left to die in the locker is what the rest of the student body calls "Jesus trash": Not because they're necessarily Christian, but because they don't participate in the predatory schemes all around them that offer some chance of survival. "[I]t was like they wanted to be crucified," Johnny says. Johnny does survive, after drinking the blood of the dead girl, and we have optimism that his will to survive will extend past his current ordeal to his life in the cruel society aboveground.

I realize that I'm both saying "this is a hopeful story with faith-based themes" and "the kid drinks the dead girl's blood in the abandoned locker room." As I said, I love this era of horror SO MUCH.

Wellspring by Lee Moler

Synopsis: A businessman gets his kicks hunting his former employees in the polluted no-go zone. But things--and people--are changing. . .

Thoughts: We're back to the self-satisfied and over-written splatterpunk zone here. I'm a sucker for toxic waste eco-horror from this time period, so I'm tempted to cut it some slack, but there's some iffy writing.

"This was where the deals went down in elevators and up in smoke. Here was where the players gave each other the triple-speed double cross while they ate hundred-dollar lunches and watched the cabs bleat at each other like poor people."

Oof. And, later:

"Self-hatred allowed him to serve as an example, a warning, a raven perched on the shoulder of society. So he crucified himself with bourbon and hung himself on the hill for all to see, but they preferred to look away. And rather than endure their ignorance, he preferred to sail down the river of whiskey and out onto the alcohol sea, where waves of vodka washed him into storms of hair tonic and Sterno then onto the shores of a cistern in a factory's basement."

I'm not sure what the solution to this sort of thing is. Mandatory licensing and training, plus a cooling off period, before you're allowed to purchase and use a metaphor?

My other problem with this as a story is similar to the issue I had with "Will Work 4 Food" last week: Once your bad-guy protagonist starts hunting people for sport, he kinda has to die. The stab at redemption--both for Rhodes, our protagonist and for The City--that's in the final paragraphs is interesting, but it would require Rhodes to be less evil.

Let's talk about that redemption, because here's where Moler's moral is very of its time: It's identifying the transition in the American economy occurring around this time that saw manufacturing and industry decline and the financial and service sectors rise. Early on, Rhodes notes that "[p]aper property was bought, carved, parceled, shipped, reconstituted, and put into play again. Today it was a service economy--a big card game where the deck was reshuffled after every pot." Later, Rees (one of the mutant vagrants) writes about feeling the emptiness at the core of The City. "He could. . . feel the paper walls and subcode foundation laid by crews of cokeheads bossed by political nephews. He could feel the new city shake in the wind and know that it was afraid of the dark to come when the suits with the play money went to play somewhere else."

At the end, Rhodes' penance is to become productive for The City: "Make something that feeds the city iron and steel instead of paper and promises." In the context of the story, it's implied that this is "something beautiful," whatever that may be, as long as it's made of steel. And this is already interesting: Usually, the 'living city' in these horror stories requires a sacrifice of blood (think "The Whimper of Whipped Dogs" or "The White Man", among others). But it makes more sense that the city would want something nourishing of its own nature: Metal. And, it's easy to read this as an allegory for the American economy--the poor are begging the capitalists to return the economy to a system based on real people producing real, tangible things, things that require steel and iron. That's why, as much as I ragged on the writing earlier, "Wellspring" has a lot of political relevance.

Query whether the solution to The City's industrial pollution problem is reindustrialization, though.

At the End of the Day by Steve Rasnic Tem

Synopsis: At the end of the day, a delivery driver has one final delivery to make. He's lost and confused, but soon he can go home.

Thoughts: It's left uncertain whether our protagonist will make his final delivery, but you know who does deliver? Tem! This is a gorgeous prose poem,

This story also does a good job of exploring the moral claims society places on us. It's similar to "Ash" (and Tem's own "The Poor", as mentioned earlier), although there's more empathy than abjection here: The driver wants to go home, but he also recognizes his responsibility to the unknown recipient of the package, who needs to receive it before they go home. This tension--between the rights of the driver to have his private life, and the rights of the recipient to have theirs--is fundamental to organized society.

There's little horror content here--although the cityscape here is often grim and unfamiliar, this isn't the concrete nightmare of "City Fishing." It is a dark work, but it's also gentle and soothing.

Des Lewis, writing about Tem's "The Poor" (which we discussed earlier) wrote "I am genuinely convinced that Rasnic Tem is THE poet of our times, one that has been hidden in plain sight or disguised as a writer of genres he is more famous for."

He's not wrong.

The Ash of Memory, the Dust of Desire by Poppy Z. Brite

Synopsis: A man takes his lover to an abortion clinic, but they wind up taking a wrong turn.

Thoughts: I saved this one for last; I knew it had gotten a Stoker nomination and that it's generally one of Brite's better regarded early stories. I'm glad I did; I liked it a lot.

There are some stories--this is one; Charlee Jacob's "The Plague Species," which I raved about last week, is another--where the quality and lushness of the writing is so intense that I despair of capturing it in my own write-ups. Pictures may be worth a thousand words, but these are words which are worth thousands of words.

This is a sensual story. Not just in terms of sex, but in terms of food. And, sometimes the food focus in Brite's work doesn't do it for me, but this is exquisite. When it arrives, the horror is also beautiful.

Hell Train by Gary Raisor

Synopsis: A New York transit worker stumbles upon a train line to Hell.

Thoughts: More straightforward horror than much of the other stuff. Not at this point new: Monsters in the subways along with portals to hell has been a theme of some great splatterpunk: John Shirley's Cellars, Skipp and Spector's The Light at the End, and Clive Barker's The Midnight Meat Train. This isn't up to those standards, but it's a fun ride. I'd read a novel-length version of this one.

This is an interesting choice to close the book, because my assumption is that, unless you're organizing an anthology by something like chronology or alphabet, you're making a statement with the last story you choose in a book. I might be wrong--for all I know, Raisor's story is last for some logistical reason--but let's assume I'm right. Let's also assume you don't mind some spoilers.

Our protagonist, Stan, jumps onto the Hell Train to save the souls of his wife and their unborn child. Raisor doesn't show how that happens (a pity, and another reason this should have been longer), but it's later implied that it worked. Stan's friend Manny dreams of Stan reunited with his family. "The night was cold, filled with stars, and the train was far away from any city. The smell of new-mown hay was in the air."

It's interesting, then, that the book's ultimate vision of hope (it occurs to me, now, this may be why Olson and Silva placed this story last--it has one of the most explicitly hopeful endings) does not involve reforming or saving The City, but escaping from it back into an explicitly rural/agrarian society. It's a reactionary ending to a complex (and sometimes, frustrating) collection of stories. I really wish they'd been able to do the other two volumes in their proposed trilogy, but if this is what we're left with, well, there's a lot to think about.

Comments

Post a Comment